In the late 19th century, Japan, which had isolated itself from the outside world for two and a half centuries, was confronted with the need to rapidly modernize, and even Westernize, to ensure its survival. As it did so, it was awakened to the value of increased trade with its neighbors and territorial expansion to facilitate its own resource needs as it industrialized.

Korea, Japan’s nearest neighbor and an historical source of cultural exchange (not to mention the target of Japanese annexation in the late 16th century), was a logical first choice for Japan’s trading ambitions. Interestingly, in extracting its first modern trade treaty with Korea in 1876 Japan employed the same kind of “gunboat tactics” against Korea that the Americans had used against the Japanese two decades earlier.

To maintain dominance of Korean trade and eliminate competition from China and Russia, Japan engaged in a series of wars (1894-95, 1900, and 1904-05), gradually establishing itself as a major force in Asia to rival the great Western powers. In 1905, Japan declared Korea its protectorate and finally in 1910, it annexed Korea amid predictions by Japanese scholars that Koreans would readily assimilate to Japanese cultural ways.

Although Japan continued to control Korea until the end of World War II (indeed, August 15, the day the Japanese surrendered ending World War II, is celebrated in Korea as National Liberation Day), the Koreans did not assimilate. Instead, they undertook various efforts over the years to assert their independence from the Japanese.

The Sam-il Movement that arguably launched all subsequent Korean independence movements began on March 1, 1919 (“sam-il” is Korean for “3-1”). The movement was initiated by Korean students inspired by American President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” speech at the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919, which advocated self-determination for all peoples. (Sadly, the Americans did not support these Korean efforts toward self-determination.)

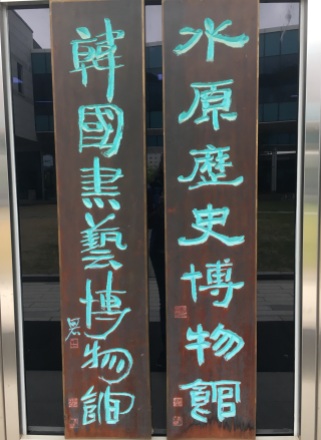

This being the centenary of the Sam-il Movement, the Suwon Museum in Suwon, Korea (about 35 kilometers south of Seoul) has a special exhibit on the movement through June 9, 2019. While Japanese museum displays on Japan’s colonization and trade with Asian countries during the 20th century portray Japan as a liberator, freeing its Asian neighbors from Western domination, this exhibition tells a different story.

The exhibit begins with some basic displays on the Korean military at the turn of the century and various symbols of Japan’s occupation.

It goes on to put Japan’s annexation of Korea into a global perspective and also offer insights into the conditions in Korea at the time.

The central feature of the exhibit is displays on gisaeng women of Suwon who played a particular role in the Sam-il Movement. Gisaeng are women entertainers, comparable to the geisha of Japan, particularly insofar as they were often from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and had been sold into the servitude of becoming gisaeng. They were then trained in various entertainment arts–singing, dancing, musical instruments–in order to work as gisaeng.

After the initial “declaration of independence” by the students in Seoul on March 1, 1919, demonstrations erupted nationwide. It is believed there were as many as 1,500 anti-Japanese demonstrations with as many as 2 million people participating. Nearly 8,000 Koreans are believed to have died in the aftermath, which also saw some 46,000 arrests. Ringleaders who evaded Japanese capture fled to exile in China and the Soviet Union’s far east.

In the Suwon area, the demonstrations were often organized by gisaeng women, many of whom were among those arrested. The exhibit includes Japanese arrest records and mug shots of the women.

Apparently even the arrested women were not cowed by their experience. There was a display about women (including the two shown above) who staged a demonstration inside their Seoul jailhouse (still extant) on the first anniversary of the Sam-il Movement.

There was also a substantial display on several of the gisaeng women who participated in various independence movements both in 1919 and later, with their photos and brief bios of their accomplishments as gisaeng. Most were in their late teens and early 20s. The “posters” are written predominately in Japanese, with just a bit of Korean for the names of the women. Although I couldn’t be sure, they looked like leaflets advertising the services available from the women in their capacity as gisaeng.

It is said that the Sam-il Movement only made things worse for the Koreans, as Japanese repression became ever-harsher in subsequent years. Yet the insurgencies continued.

Two Suwon women featured were arrested in Seoul for their involvement in a movement in the mid-1930s. Although there are records of their arrest and charges against them, their ultimate fate remains a mystery. There are no records of what became of them after four months’ incarceration. Neither had reached her 20th birthday when she disappeared.

Koreans finally gained their independence from Japan in 1945, only to plunge into civil war shortly thereafter, soon to find itself torn apart by outside powers. Yet, as this headline, on a newspaper found in the museum’s displays on the history of the city of Suwon, explains, Koreans find a way to go on.

And although there are still some unhealed wounds, relations between Japan and Korea are certainly more positive, and on a more equal footing, than they were a century ago.

- Address: 265, Changnyong-daero, Yeongtong-gu, Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do

- Hours: 9:00-18:00 (Last admission 17:00) (closed first Monday of every month)

- Admission: KRW2,000 (adults); KRW 1,000 (teens); no charge for children or seniors (Note: there is an integrated ticket including admission to Suwonhwaseong Fortress, Hwaseong Haenggung Place, Suwon Museum, Suwon Hawaseong Museum at a substantial discount – ask at the ticket counter for details)

© 2019 Jigsaw-japan.com and Vicki L. Beyer

We’re thrilled if you share a link to this page; if you want to re-use in any other way, please request permission.